This report explores the deep divide over the status of social media platforms. Current law tends to confer on these entities extensive immunities from liability for removing any content the platform deems is a form of misinformation, and the law allows the platforms to ban private parties from the platform or demonetize their platform’s use. The stated reason is that these platforms are private parties that are therefore not subject to regulation, given the protections they received under both common law and the First Amendment.

This position has provoked a vigorous response from those who believe these platforms should be regulated as common carriers because of their dominant position and should be subject to potential antitrust liability because of their collusive behavior or subject to liability because of their close cooperation with the federal government in censoring content. Proposed remedies include limiting or removing protection under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and holding platforms liable for defamation when these actions are done in bad faith, as is the case when done with obvious political motivations. Texas Law H.R. 20, a recent attempt at such a remedy, proposes extensive disclosure requirements and a nondiscrimination rule to protect dissident voices.

These issues require some fresh thinking to break the impasse. In this report, I propose that it is unwise for anyone to make all-or-nothing judgments about the status of social platforms. In the long run, the prospect of new entry might make social platforms competitive. But in the short run, no such entry has impeded their power, so they might well be properly subject to some regulation as common carriers. But of what sort? I think that elaborate disclosure requirements serve little purpose (as is so often the case in securities law), and they could be struck down even if these parties were regarded as common carriers or extensions of the government. But nondiscrimination requirements are both less intrusive and more effective, and these in turn should be upheld, at least until the industry becomes more competitive through new entry.

In addition, branding an individual or firm as purveying misinformation is a serious charge that brings people into disrespect and otherwise deters customers from listening to or acting on what these platform messages say. That defamation should be actionable even under New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) if it can be shown (as often will be the case) that the social media platform did so with reckless disregard of the truth or with knowledge of the falsity of the statements. In addition, there is no need to alter the text of Section 230 because these decisions cannot be regarded as having been made in good faith when they are all designed to back the political agenda of the Biden administration and its allies.

The role of social media platforms is now under scrutiny as perhaps never before, particularly as their content moderation practices raise several legal questions. Should any platform have the right to limit or deny access to its users by adopting strategies of content moderation, suspension, or removal? Or are these platforms subject to liability on any number of grounds—breach of their own contracts of service, the antitrust laws, the First Amendment, or even the law of defamation? There are many strands to the argument, but the best first cut to the problem draws on the neutrality principle—a nondiscrimination rule that has long been imposed in connection with common carriers and public utilities. That principle, although originally a comprehensive mode of regulation in the economic sphere, can be applied as well to the content of speech.

My claim to notoriety on this subject starts with the interview I gave on January 15, 2021, with Tunku Varadarajan in the Wall Street Journal. In the interview, I discussed the common-carrier model, which tends to favor the use of neutrality principles.1 In other words, common carriers usually cannot discriminate without just cause between the passengers and goods they carry. Analogously, platform limitations can constitute viewpoint discrimination that restricts the freedom of targeted platform users to reach the public at large.

My interview with Varadarajan has attracted more attention, and more disapproval, than is common for op-eds. My suggestion was that those common-carrier rules might provide an alternative to any hard-line position that insists the government must always keep its hands off internet platforms, as Matthew Feeney urges,2 or that it should wrap an iron fist around these platforms, as advocated by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO),3 whose proposed legislation, Limiting Section 230 Immunity to Good Samaritans Act,4 leaves little to the imagination. The bill’s preeminent purpose is “to amend the Communications Act of 1934 to provide accountability for bad actors who abuse the Good Samaritan protections provided under that Act, and for other purposes.” In my view, both of these positions take an oversimplified approach to a problem that is hard, precisely because of the many crosscurrents in this area.

My basic position also attracted attention from the Supreme Court. In Biden v. Knight First Amendment Institute (2021), the Court dismissed as moot a Second Circuit decision that had prevented former President Donald Trump from blocking critics from his Twitter account on First Amendment grounds.5 In his concurrence, Justice Clarence Thomas placed the common-carrier issue front and center. Twitter states in its terms of service that Twitter can remove any person from the platform—including the president of the United States—“at any time for any or no reason.”6 Justice Thomas responded, “There is a fair argument that some digital platforms are sufficiently akin to common carriers or places of accommodation to be regulated in this manner” because they are “highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure.”7 Twitter’s contractual power to exclude would be invalid under established common-carrier principles that require services to be extended to all on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms, sharply limiting the right to remove.

This common-carrier argument requires some elaboration, so I shall now draw on much of my previous work on the regulation of common carriers.8 Common-carrier regulation was first introduced in the 17th century by Sir Matthew Hale, and it was later carried into English law by the key case of Allnutt v. Inglis (1810),9 which in its own way was a marvel of precision. It accepted the general principle of freedom of contract but refused to impose it in a case in which the natural limitations of the physical site meant that only one crane could operate, so that from the outset legal and physical restrictions were treated on a par. Indeed, one unexpected if fundamental term in that analysis—“virtual” monopoly—made its way across the Atlantic when Allnutt was incorporated into American law in Munn v. Illinois (1876).10

Extensive constitutional literature subsequently developed on the proper mode of regulation of these monopolies—especially, but not exclusively, on rate-of-return issues. Accordingly, a general view of social relationships divides all interactions into two broad categories: coercion and consent. It is generally agreed that the latter is preferable to the former. To many libertarians, this is a self-evident truism. But to those of us who are more concerned with consequentialist theories of the world, the explanation runs as follows.

Where there is coercion, we know that one side will be better off, while the other is worse off. At this point, two conclusions can be reached. First, if one thinks in terms of Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, the coerced party likely loses more than the coercing party gains; just think of a murder-for-hire case. Second, if one thinks in terms of Pareto efficiency, it is not possible to find any mutual gain out of these exactions. In contrast, voluntary transactions—those without coercion or misrepresentation—produce mutual gains for both parties and thus satisfy not only the less rigorous Kaldor-Hicks standard but also the Pareto efficiency standard. String together a set of these transactions, and the sky is the limit for social gain, so long as we can keep transaction costs low enough to allow these markets to prosper.

Against this backdrop, it is worth noting that today the level of scrutiny given to various forms of government regulations on speech tends to be higher than in other areas, most notably the protection of property against confiscation. Nonetheless, First Amendment jurisprudence does not hold that only actions like threats of force or defamation are subject to sanctions. The question of monopoly power has always been a touchy one for First Amendment theorists.

In the area most relevant to this problem, the First Amendment does not currently insulate (as in principle it should)11 newspapers from being unionized. Instead, general collective-bargaining tropes take over. As early as 1937, management—under Associated Press v. National Labor Relations Board—was subject to mandatory rules on whom to hire and was forced to negotiate work rules that could impede its ability to tell its own story in its own way.12 In my view, this progressive innovation is flatly inconsistent with the First Amendment (and, indeed, the takings clause, because it converts a competitive market into a monopolistic one).

In 1945, moreover, the Supreme Court held in Associated Press v. United States that the First Amendment in itself did not exempt the Associated Press from antitrust laws.13 I regard this decision as correct precisely because the Sherman Act’s purpose to control monopolization efforts was uneasily reconciled with only Section 6 of the Clayton Act,14 which held that unions and agricultural cooperatives had a limited but important exemption from antitrust laws.

For these purposes, however, we have to take the law as it is. The evident contrast in these cases makes it harder to claim that common-carrier regulation is necessarily out of bounds. Like antitrust law, common-carrier regulation is meant to deal with the problem of monopoly power. Unlike antitrust law, it deals with situations in which breaking up the monopoly is technically infeasible because of the efficiencies lost from dissolving a unified firm. The question in those situations is whether some degree of regulation is permissible or whether the problem should lie without redress. The historical record is clear: As Matthew Hale explained in De Portibus Maris, any party that holds either a legal or a natural monopoly falls under a duty to provide services to all comers on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms.15

This position developed to decide what was to be done if an inn or a carriage was the only shop in town and could refuse to deal with customers. Within the libertarian framework, contracting parties are entitled to accept or refuse business for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reason at all. That position works exceptionally well in competitive markets and has led to the widespread acceptance (at least as a common-law matter) of contract-at-will employment, which does exactly that.16 The refusal to deal, however, takes a more ominous turn when there is no readily available alternative, which was (at least early on) the case with common carriers. Thus, a more complex scheme must be devised.

Forcing a customer on a carrier without any compensation is a wholly unstable policy. Carriers have expenses that they can recover only from the revenues derived from their business. These revenues must be sufficient to cover their costs and must be fairly apportioned across the various users. Thus, the word “reasonable” is directed at keeping the total revenues in line—large enough to cover costs and yield a risk-adjusted fair profit but not so large as to generate monopoly rents. And the term “nondiscriminatory” is intended to secure the proper distribution of those costs across a given class of users, such as peak-load or off-hour users, in proportion to the costs expended to deal with that class. Where rates are involved, the calculations are intricate to say the least, but the motivation for them is clear. In any event, the refusal-to-deal framework is wholly inadequate to deal with this situation, so the quasi-administrative solution has to be put into its place to set total revenues and apportion them among the various classes of users.

Libertarians, including John Samples, have argued that the entire problem of the common carrier is something of a fiction.17 For Samples, the power of new entry is such that parties that are not happy with the status quo ante can take their marbles and play on someone else’s field. Competition is the normal state of the world, and regulation championed in the name of advancing competition turns out all too often to stifle it. Samples’s remarks are made in connection with First Amendment issues, not economic ones. But the power of free entry in dealing with traditional public utilities and common carriers is generally limited. These industries require large upfront capital investments and have costs that must be recovered over many years and be fairly apportioned among parties.

In general, it would be a mistake to dismiss this problem and the solution posed out of hand. The optimistic view that these industries will become competitive over time has often proved incorrect, as so-called “natural monopoly”18 industries have declining marginal costs over a large portion of the supply curve, which means that cramming two entrants into that single physical space is more expensive than having just one. At that point—and in line with the well-known analysis of Harold Demsetz in “Why Regulate Utilities?”19—the hard trade-off is between a system that limits rates in the short run to control against monopoly profits, even if in the long run it stifles dynamic competition from new entrants with disruptive technologies. With certain stable industries, the former position may appear attractive, but there is no reason to enter into that dispute here. What is clear is that the rate of technical innovation is far higher in the modern internet age.

The hard question is the extent to which this model carries over to the modern issues connected to the First Amendment. The urgency of the situation is clear: The current set of dominant social media carriers all have a liberal or progressive bent—think Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter—and have used their power to selectively remove conservative thought from their platforms. The evident harm from this arrangement in the short run is that it skews the public debate, as these outlets assume the power to judge which material passes through their portal and which does not.

In many cases—and this point will become key—these removals have serious justifications (for example, where the company makes a specific finding that these individuals are engaged in the instigation of terror or insurrection). But in other cases, the grounds for removal are far vaguer and more controversial—namely, the propagation of “misinformation.” The term “misinformation” can be applied so literally that it comes into tension with the normal guarantees of fair treatment that may well be read into the company’s standard terms-of-service agreement, which does nothing to disclaim them.20 The removal is purportedly neutral but seemingly ideological. Anti-regulation advocates argue that other sites will provide alternatives where there is sufficient demand, so the market will prove to be rational in its control over particular cases even if the individual players within it are not.

The industry-wide debate on common-carrier status indicates a wide split of opinion. On the one side are organizations like NetChoice, a self-described lobbying organization that claims that the First Amendment protects all the dominant internet operators from any speech-related form of government regulation, either state or federal.21 On the other side stands the New Civil Liberties Alliance, which emphatically takes the position that long-standing common-carrier guarantees place powerful limitations on the ability of these dominant institutions to be treated just like private parties.22

Of these two positions, the judiciary has unfortunately blindly accepted the former without seriously engaging with the latter, as shown by cases such as O’Handley v. Padilla (2022), which baldly announced that “Twitter is a private entity” without once examining the potential applicability of the common-carrier doctrine.23 At issue in that case was Twitter’s Civic Integrity Policy, which prohibits posting “false or misleading information intended to undermine public confidence in an election or other civic process.”24 Twitter decided that Rogan O’Handley violated that policy by posting fraud charges against high California officials in the conduct of the 2020 presidential election, and it removed his posts under this standard.

The most thorough—and in my opinion, entirely incorrect—judicial discussion of the common-carrier issue to date has been that of Judge Robert Pitman of the Western District of Texas in NetChoice v. Paxton.25 This case tested the constitutionality of the recent Texas statute H.B. 20, which purports to address censorship by social media platforms against individuals with dissident views.26 As is typical in this area, both the parties attacking the regulation and those defending it sought to clothe themselves as champions of the First Amendment. H.B. 20 states that “each person in this state has a fundamental interest in the free exchange of ideas and information, including the freedom of others to share and receives ideas and information.”27 Texas submitted a report drafted by Professor Adam Candeub, who concluded that social media platforms did indeed possess sufficient market power to qualify as common carriers.28 NetChoice, of course, argued that the platforms could best protect this interest through exclusive control over their own operations, including the power to ban posts they think represent various forms of misinformation.

In NetChoice, the District Court first held that the platforms had the right to exercise editorial discretion, which included excluding certain offensive or inappropriate materials from their sites.29 That finding did not just refer to outright defamation or obscenity but covered a broad category of “misinformation,” a classification that has no parallel in traditional rules for common carriage. From this observation, the court leapt to the conclusion that these platforms could not be common carriers because they do more than facilitate the transmission of speech to others.30

But that reasoning puts the cart before the horse, as the question of who counts as a common carrier depends critically on market structure. In this case, the key question is whether the defendant in question sufficiently controls the outlets for dissemination such that potential content providers have few, if any, equally attractive alternatives to place their work. If so, then there is no place for their so-called editorial discretion beyond the narrow bounds that long have governed traditional common carriers.

The District Court relied on a number of decisions that defended the right of autonomous institutions to pick their own associates and choose their own messages, but none of these cases actually involved common carriers. For instance, Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974) involved a newspaper’s right to grant a right of reply to persons who objected to its editorials.31 Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston (1995) involved the right of the sponsor of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Boston to exclude gay groups from its floats under their own banners, given that it (unlike the Boston streets) did not operate as a common carrier covered by the Massachusetts public accommodation laws.32 And Pacific Gas & Electric Co. v. Public Utilities Commission of California (1986) rejected the claim that the unused space in one of Pacific Gas & Electric Co.’s billing envelopes should be made available to public groups.33

Indeed, if these carriers do enjoy that level of discretion, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act would relieve them of liability for statements made by their users.34 Section 230(c)(1) states, “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” Section 230(c)(2) then exempts platform companies from liability for

any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.35

These protections are meant to insulate these websites from liability for the billions of messages that pass over their platforms each day. But it is an open question whether material that is “otherwise objectionable” is broad enough to cover all sorts of medical and scientific positions that various platforms remove or limit. The matter is especially urgent when the viewpoint discrimination affects issues for which it is crucial that dissenting voices be allowed to criticize the dominant position, such as the risks of global warming or the efficacy of mRNA vaccines. At some point, active intervention should demonstrate that these actions are no longer taken “in good faith” and are thus no longer shielded by the statute.

The analysis of social media platforms is more complex than for conventional internet services for two reasons. First, there may be so much cooperation between the platforms and any government protection that the platforms are converted into government actors subject to constitutional constraints.36 Second, the platform operators may be operating in concert with each other, so that ordinary antitrust principles of horizontal collusion apply. Whether they actually collude is a tricky question not made any easier by the simple point37 that there is ample public signaling by all the key social media platforms in pursuing substantially identical policies.

It is also necessary to ask whether any such conscious and public parallelism makes it permissible to aggregate the activities of each of the dominant players, such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter, whose policies are scarcely distinguishable from each other. The pattern of inference is at the very least simpler than that required in the best-known case dealing with price signals, In re Coordinated Pretrial Proceedings in Petroleum Products Antitrust Litigation (1990),38 because it is far harder39 to draw inferences of price coordination from public shifts in pricing a “sawtooth” pattern, which may well be pro-competitive. But these signals are clear and unambiguous, and if the Biden administration is seeking to expand the scope of the antitrust law by executive order,40 this kind of case fits the bill.

Once the common-carrier and antitrust issues were put to one side in NetChoice, the First Amendment analysis quickly fell into place: The amendment does not govern private speech. But if the common-carrier approach is taken, the First Amendment issues implicated by H.R. 20 are cloudier. Texas introduced two forms of regulation in that law. The first requires that the platform “publicly disclose accurate information regarding its content management, data management, and business practices, including specific information regarding the manner in which the social media platform” discharges a large list of functions, backed by an elaborate mandatory complaint system.41

Burdensome disclosures such as this are common in the securities industry, including most recently a proposal to require disclosure of not only a company’s own greenhouse gas emissions but also those of their suppliers and customers.42 To my mind, these approaches are surely miscast in securities cases and ridiculously inappropriate for social media companies. I know of no such extensive regulation of ordinary common carriers and think that these should be off-limits and unconstitutional in this context.

Yet the second form of regulation in H.R. 20—namely, the effort to stop platform censorship based on viewpoint discrimination—does not suffer from similar administrative impediments. There are no front-end reporting requirements, and the examination can be made on the strength of publicly available information.43 If the media companies had been government-run, viewpoint discrimination would be subject to per se condemnation. So, if the social media platforms engage in viewpoint discrimination either alone or in combination and they are considered common carriers, then the statute should be easily sustained on this title, even if the data collection provisions are struck down.

So again, we are back to the central question of how to determine the status of these social media platforms as common carriers. At the outset, we know that natural monopolies have lasted a long time in a number of industries, where the technology is static enough that rate regulation becomes part of the landscape, such as with gas and electricity. It is a fair response that the rapid turnover in internet companies counsels strongly against any intervention. On the other hand, the current titans of social media have percentages of market share that have held up pretty well—at least in the short run.

In my experience, there is no easy answer to the empirical question of how long a firm faced with open entry can keep its dominant position.44 The argument against regulation is that there are really no natural monopolies in this space, so it is best to let matters ride. But the great weakness of that solution is that it is unknown how long it will take for the process of free entry (and exit) to work its magic. Reluctantly, I tend to think the process is likely to take years, not months, but as I have little confidence in that judgment, I prefer to adopt another approach to the basic problem.

The basic logic of this latter approach is that we do not have to know the durability of these (supposed) monopolies to come to a workable compromise. There is far less difficulty in calculating the current shares of the market that are held by different firms. Far greater difficulty comes in any extrapolation of this knowledge to the rate of decay of their monopoly power. Of course, there is the problem of whether we should treat these shares independently on the ground that the firms have no cooperation with each other. I am uneasy about that given that tacit collusion is a constant theme in this area and is bolstered by the uniformity of the substantive conditions taken. Even if the aggregation is allowed, moreover, the rate of decay will likely be slower, meaning that problem looms larger for longer.

But let us suppose that some judgment must be made on this question. At this juncture, I think the key to success in this area is to come up with short-term solutions that do not require any estimations of what that rate of decay might be. Take it one slice at a time—say, for six-month intervals. So long as the concentration ratios remain above some general norm, then we apply the common-carrier rules to these companies for the want of an appropriate substitute. When new entry comes and the numbers fall, then we revert to the normal rule that does not require any individual or firm to do business with anyone else. There is no need to make any front-end estimation of when that change occurs; just follow the results and see what happens in terms of the arrival of new entrants and their ability to garner market shares. The irony here is that the established firm may well decide that it will back off just a bit to allow competition to flourish in order to escape any common-carrier obligation. How all this works out if market shares go both up and down in various settings is at this time wholly unexplored.

A second approach to this problem has nothing whatsoever to do with market share or durability. Instead, this approach addresses whether statements that accompany the removal of material or even the removal of the material itself from a website constitute a form of actionable defamation. Given current law, it will be difficult to make out that case.

Under the general rule set out in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), a public official or public figure must prove actual malice, in the sense of knowing falsehood or reckless disregard for the truth.45 Perhaps an even greater barrier lies in the doctrine of mitior sensus, or innocent construction, which allows parties to escape liability for statements that are commonly understood as defamatory because there exists some alternative interpretation reasonably capable of some innocent construction.

Take, for instance, the well-known case of Lott v. Levitt (2009) between two influential economists, which held that the statement that others could not “replicate” the plaintiff’s results could be innocently read to mean only that others had used different methods to reach the same result.46 But that is not a credible reading when the failure to replicate appears in the paragraph that asks rhetorically whether Lott had “actually invented” his results or whether they might be “faked.” Context really matters, so it is dangerous to conclude that a statement is not defamatory if it is true in isolation but false in context—a position that is at complete odds with the view of false statements under the securities law.47

Nonetheless, a return to the earlier common-law view48 on the subject seems preferable and now seems to be gaining some renewed traction.49 In my view, when someone says that another has engaged in disinformation, that assertion creates a prima facie case of defamation, such that those statements should be denied First Amendment protection. It is a form of defamation to call someone a terrorist or say they have shown disrespect to various persons or ethnic groups. At some point, statements like this cease in my view to be mere statements of opinion, which are absolutely privileged. The historical line has usually been drawn to protect any description of someone as a criminal of some sort under one of two conditions—either the background factual premises are so well established that they need not be stated or the speaker lays out, accurately, the evidence that is used to support that charge.50

There may well be lots of disagreement as to how these two elements interact, so that any movement in this direction would have to be slow and cautious. But if a website condemns anyone who disagrees with the established narrative on the proper response to COVID-19, those actions come close to or cross the line and become actionable defamation—all the more so if it is targeted against a given individual, with the clear implication that their professional views are socially dangerous.51

Take a real example: MedPage Today denounced52 the three major sponsors of the Great Barrington Declaration—Jay Bhattacharya, MD, PhD, of Stanford; Sunetra Gupta, PhD, of Oxford; and Martin Kulldorff, then PhD, of Harvard. The declaration had argued against the total shutdown of the economy in favor of what they term “focused protection.”53 It is certainly proper to disagree with that view, but it is an open question whether Francis Collins and Anthony Fauci crossed the defamation line when they denounced these individuals as fringe scientists.54 Collins wrote:

This is a fringe component of epidemiology. This is not mainstream science. It’s dangerous. It fits into the political views of certain parts of our confused political establishment. . . . I’m sure it will be an idea that someone can wrap themselves in as a justification for skipping wearing masks or social distancing and just doing whatever they damn well please.55

There is not the slightest recognition that the alternative position—that masks are useless or dangerous and social distancing is only a mirage and that strong measures likely curtailing access to medical and hospital services are irresponsible or worse—may well have been correct. This is not the place to debate those issues, but it is worth noting that a recent Johns Hopkins study concluded that lockdowns only reduce mortality 0.2 percent at huge economic cost.56

Deciding whether these ad hominem criticisms, alleging a corrupt political motive, rise to defamation is no easy matter. But Collins and Fauci have undoubtedly committed a true disservice to open intellectual debate by using established media outlets and government scientists to silence their opponents, especially when it seems now (as, frankly, it seemed then) that they are wrong. Today, these remarks could not support any case for actionable defamation, but under a more responsible system, the outcome could well be different.

The battles over the proper response to the virus are only one chapter in the COVID-19 epic. The second side to the debate asks whether the virus originated from a leak at the Wuhan Institute of Virology or the local wet markets in Wuhan. A learned Forbes article on June 3, 2021, attacked the lab-leak theory as a straight conspiracy.57 It berated Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) for vilifying Fauci, and it asked, but only rhetorically, whether such claims were “merely political machinations, designed to disingenuously cast blame while simultaneously justifying a wanton neglect of necessary responsibilities by numerous governments across the globe.”58 That article was promptly followed on June 6, 2021, by a rival article in the Wall Street Journal that defended the lab-leak theory on the ground that the genetic footprint of the COVID-19 virus could not occur in nature;59 further writing by Nicholas Wade has done much to confirm the Wuhan lab-leak theory.60

The ad hominem attack of “political machinations” in the Forbes article might not reach the standards for defamation under current law. But suppose a website took down the Wall Street Journal article on the ground that it was conspiratorial misinformation? That one act signals that the publication’s claim should be treated as a deliberate falsehood, which is close to actionable defamation. But does it cross the line when the lab-leak theory is proved correct, as now seems more plausible,61 and the ban still remains in place?

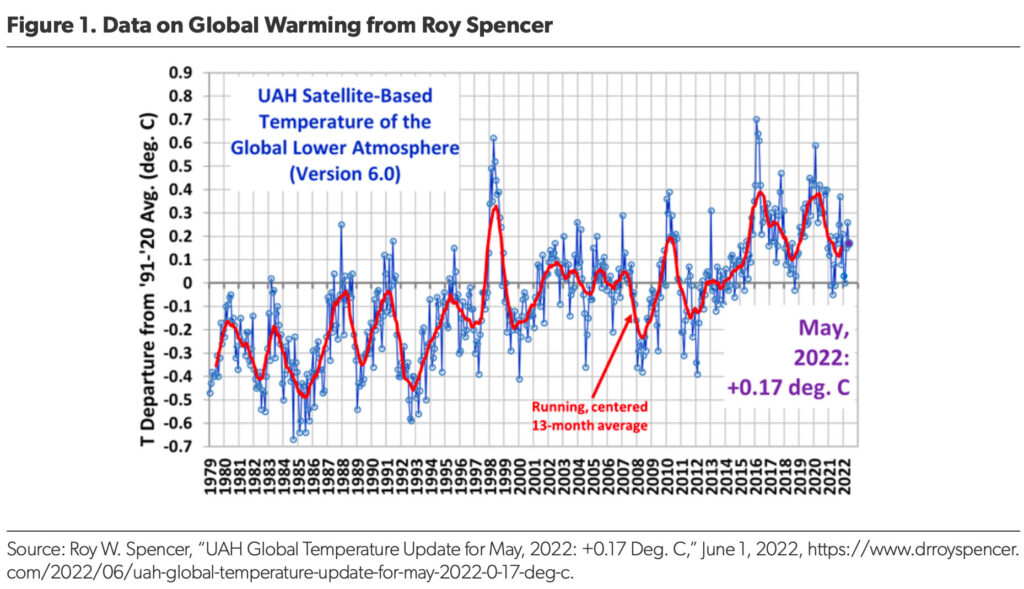

Here is another example. Google recently decided62 to demonetize Roy Spencer, a scientist who has won all sorts of awards,63 for making “unreliable and harmful claims” on matters pertaining to global warming. Undoubtedly, this remark is intended to cast aspersions on Spencer, and these words, if proved false, are defamation. The decision thereafter to block him from raising money to support his movement shows the seriousness with which the judgment is rendered. The initial question is whether these charges against him are true.

The general trend line he presented (whose data accuracy was not challenged) is shown in Figure 1. That red line does not bespeak immediate tragedy, and the zigs and zags throughout this entire period lay waste to the claim that the monotonic increases in carbon dioxide are the sole driver of climate change. It is, therefore, an open question, to say the least, whether the prominent people who call for “code red” should be the ones challenged for misinformation.64

But in this context, the more immediate question is whether removing this document for containing misinformation is tantamount to willful defamation when the available information cuts against that charge. Unlike various disclosure and reporting statutes, a defamation action does not require a media company to search its entire database and ferret out all misgivings. The focus is no longer on its general operations but the particular case of how a common carrier deplatformed a user, attached warnings to his or her posts, or imposed other such sanctions. Under New York Times v. Sullivan,65 the plaintiff would have to show that these statements were made with “actual malice”—that is, by someone who knew they were wrong. The malice issue introduces all sorts of complications,66 but it is at least plausible to argue that Google knew that its conclusion was false just by looking at the chart.

That said, I generally advise anyone who asks that they should never bring defamation suits, not because they are ill-conceived, but because they subject the plaintiff to enormous abuse through repetition of the charges and condemnation of those who defy standard norms. But if some brave soul should bring such a case, the entire matter of defamation will be concretized in a way that should put to rest the notion that social media platforms cannot cope with the huge amount of information that comes their way, given that they usually have had extensive internal review of the matter.

Ultimately, readers will also have to decide whether it is merely a simple description of one’s political position when the author tosses around the phrase “conspiracy theories.” That term suggests that the other side is beyond the pale—which should be defamatory if false. I am genuinely troubled with both extremes; either defamation never takes place, or it is subject to an absolute privilege. But, even if lawsuits cannot be brought, a public statement that certain attacks were defamatory might help focus the debate on the high risks that arise from the all-too-common denunciation of rival ideas.

To step back for a second: Every single empirical statement or prescription in this short report is subject to dispute, which is why the disputes will continue apace. No one has a monopoly on bad opinions—or good ones. Right now, the social media platform operators seem to have the upper hand. The question is whether they can maintain it going forward given the insistent and powerful challenges to their positions on intellectual and constitutional grounds.

My thanks to Christian McGuire and Samuel Milner of the University of Chicago Law School Class of 2022 for their expert research assistance.

Richard A. Epstein is the inaugural Laurence A. Tisch Professor of Law at the New York University School of Law, the Peter and Kirsten Bedford Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and the James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago.

Social Media, Common Carriage, and the First Amendment

By Daniel Lyons and Richard A. Epstein